Lungwort

Pulmonaria, Jerusalem Cowslip, Bethlehem Sage

The densely-clustered leaves of lungwort look more like hearts than lungs to me, with twin curves joining up to an elegant narrow point. They’re quietly eccentric, happiest in the damp and shade, nestling next to oak trees or burrowing down amidst leaf-litter. You spot them by their silver mottling, like a touch of frost. Sometimes it’s just small flecks, sometimes—as in a sub-species called ‘Excalibur’—covering the whole leaf, shimmering icily. For all their chilly appearance, they’re softies really, covered with fine fuzzy hairs and smelling sweetly watery, like melon rind or cucumber.

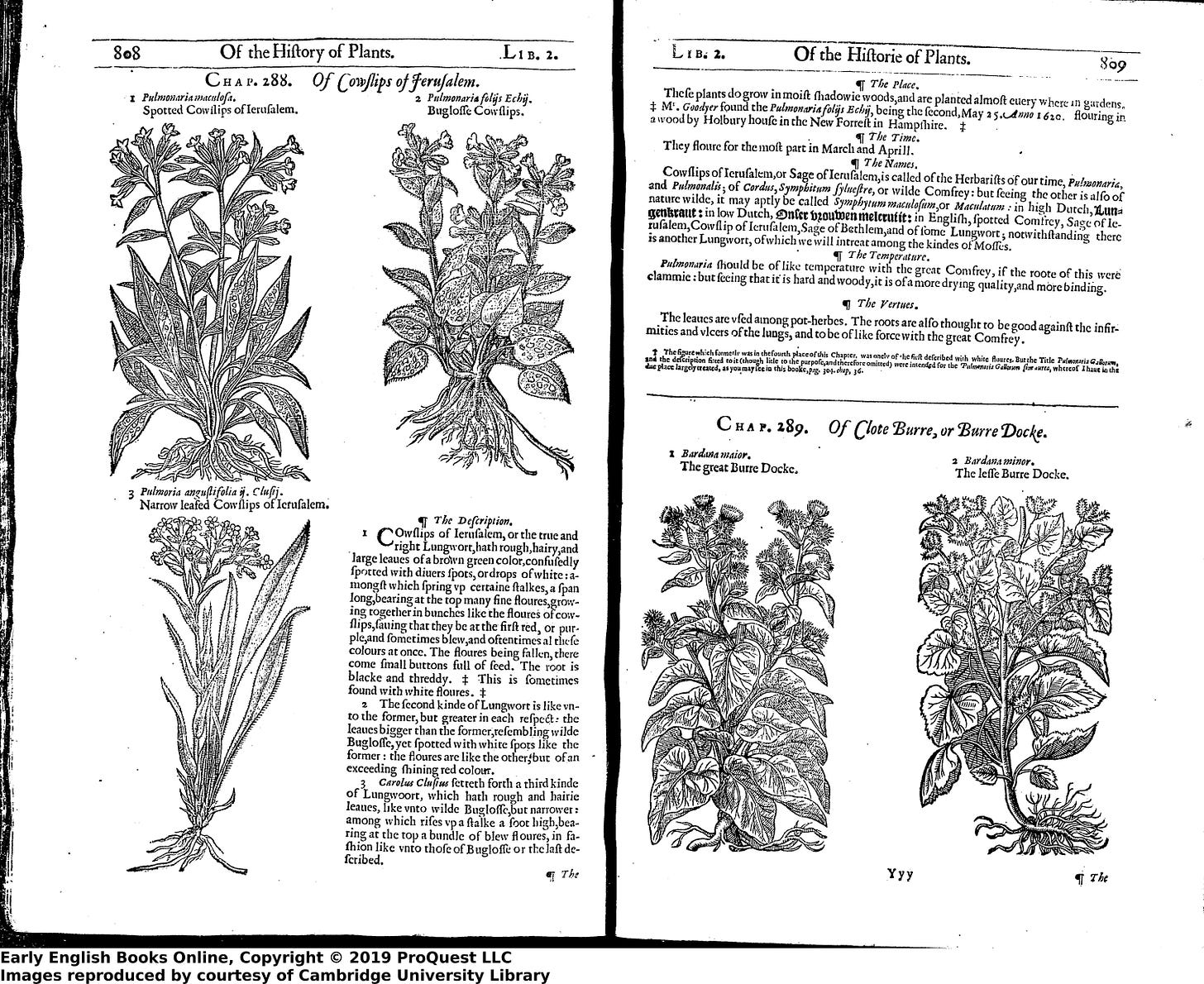

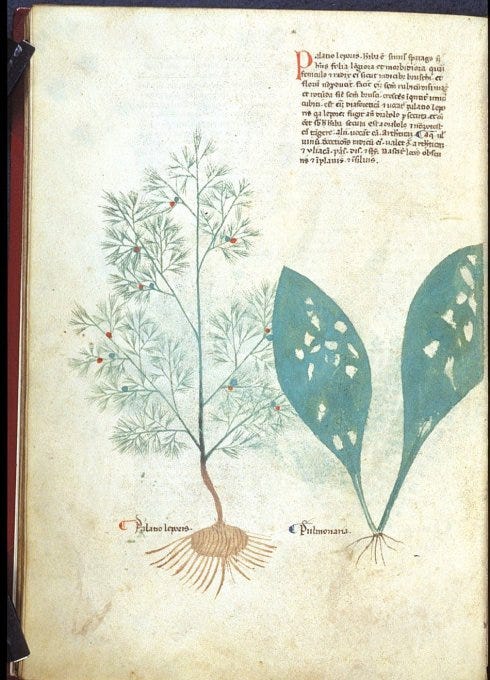

There’s a good description of lungwort in the satisfyingly alliterative Bullein’s Bulwarke (full title: Bullein’s Bulwarke of Defence against all Sicknesse, Soarenesse, and Woundes, 1562). Written by William Bullein (1515-1562), the Bulwarke contains the Booke of Simples, one of the earliest English print herbals (incidentally, Bullein was buried in St Giles’s Cripplegate, a stone’s throw from the Barber-Surgeons’ Physic Garden which inspired this newsletter, and where lungwort still grows today). “Pulmonaria,” Bullein wrote, using lungwort’s etymologically reverse-engineered Latin name, “doth grow out of the Oke tree, or stony places, hauing soft leaues, the vpperside greene, and the neather whitish, with little small bladers vpon ye crumpled leaues.” As with most of the plants catalogued by Bullein, lungwort could be used for a range of purposes: “this herbe doth close newe woundes togither: most chiefly it helpeth the Lunges, or spitting of bloude, and stoppeth termes immoderate, & the bloudy fluxe.” By the time John Gerard mentions lungwort in his own herbal in 1597, this plant with “rough, hairy, and large leaues of a brown green color, confusedly spotted with diuers spots, or drops of white” has taken on a more specific medical use, “against the infirmities and ulcers of the lungs.”

Why lungs? It’s not a universal association. In Eastern European languages, the name is derived from the word for “honey,” presumably because of the sweet smell. Bullein gives us the answer: “the whole lumpe of this herbe…is like the Lunges of mankinde.” That is, the speckled ovoid leaves look like the human lung. It’s not a resemblance that leaps to my mind. At a push it’s the kind of lung that features in photos on the front of cigarette packs, scarred and stippled. One of the images that circulated during the early part of the pandemic was a side-by-side scan of an uninfected lung and a post-Covid lung, the latter aflame with artificially-coloured blotches. Figure 1: healthy; Figure 2: sick. The sickness of lungwort leaves is less alien, more subtle: a silvery shadow, always-already part of the whole.

The idea that plants treat the body parts which they resemble is rooted in the Doctrine of Signatures, a Christian notion deriving from a deep-seated sense of correspondence between nature and the body which has operated in many different cultures throughout history. The “signatures” are divine signs, clues left to us by God that tell us how to use the tools available to us in the natural world. Paracelsus, the enormously influential physician, famously described the doctrine in 1537: “I have oft-times declared, how by outward shapes and qualities of things we may know their inward virtues, which God has put in them for the good of man.” (I wrote in the last newsletter that medicine is really all about signs and language—well, there you are). There are plenty of similar examples: bloodroot with its crimson extract for haematological disorders, saxifrage which grows through solid rock as a way to disintegrate kidney stones. Common honesty, with its translucent papery pods like little moons, was a cure for full-moon madness or “lunacy,” hence its Latin name Lunaria.

Another such plant was eyebright, so-called because of the vaguely ocular appearance of its white-ringed flowers. Towards the end of Paradise Lost (by John Milton who, as it happens, was also buried in St Giles’ Cripplegate, feet away from Bullein), the archangel Michael cures Adam’s sight, corrupted by the apple:

Michael from Adams eyes the Filme remov'd

Which that false Fruit that promis'd clearer sight

Had bred; then purg'd with Euphrasie and Rue

The visual Nerve, for he had much to see

(Book 11, 412-415)

“Euphrasie” is the English term for Euphrasia officinalis, or eyebright. For obvious reasons, Milton was painfully familiar with the detail of eye disorders and potential cures. But it also makes sense that eyebright, emblematic of the divine correspondence between man and nature, here goes some way to salving the rupture of the Fall. Of course, Paradise Lost as a whole puts the lie to the idea that we live in a rational, interpretable universe. For all that Adam and Eve are told that “Heaven / Is as the book of God before thee set, / Wherein to read his wonderous works,” they end up victims of the anomalous absurdity of the Tree of Knowledge, placed in Eden to serve no function other than as a moral test. I’ve always felt that’s slightly unfair, and I suspect Milton agrees with me. In any case, eyebright is still used to soothe eye infections. Unfortunately for those of us living through this year, lungwort has had no such therapeutic success.

P.S: Thank you to the reader who sent me this piece by Maggie O’Farrell (in, weirdly, the FT’s How to Spend It), talking about the herbal obsession that stemmed from researching her novel, Hamnet. As she writes: “there are some ailments that somehow slip through the cracks of medical wisdom, and plants can wield a mysterious power to both heal and harm. And perhaps you should always carry a penknife while out and about, because you never know what you might find.”