Christmas Special: Holly

For all the festive Victoriana, there is a beautiful strangeness to this plant

So far, the plants in our Physic Garden have been underrated gems, deserving of a little more exposure. For this special festive edition, however, we have a towering botanical celebrity: holly (ilex aquifolium). Holly’s long history of ritual significance has smothered it with successive layers of cultural meaning. It was an important symbol of fertility for pagans, decked the halls of medieval Christians, and became a central part of Yuletide iconography for Victorians. Well before the nineteenth century, holly was entwined with ideas of ancestral Englishness, making it a common feature of Renaissance pastoral romance. In Lady Mary Wroth’s Urania (1621), the first prose fiction published by an English woman, holly features prominently in a typical scene of chivalric melodrama, when a knight reveals “a large Holly tree (the place rich with trees of that kind), on which at his comming to that melancholy abiding, hee had hung his Armor, meaning that should there remaine in memorie of him, and as a monument after his death, to the end, that whosoeuer did finde his bodie, might by that see, hee was no meane man, though subiect to fortune.” In As You Like It (c.1599), Shakespeare throws sprigs of holly into the pleasantly mindless songs with which the forest-dwellers punctuate the action:

Heigh-ho! sing, heigh-ho! unto the green holly:

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly:

Then, heigh-ho, the holly!

This life is most jolly.

The rhyming of “holly” and “folly” possibly hints at a connection between holly and madness, also attested in the phrase “hulver-headed” (hulver is another word for holly), meaning “stupid; muddled; confused; as if the head were enveloped in a hulver bush.”

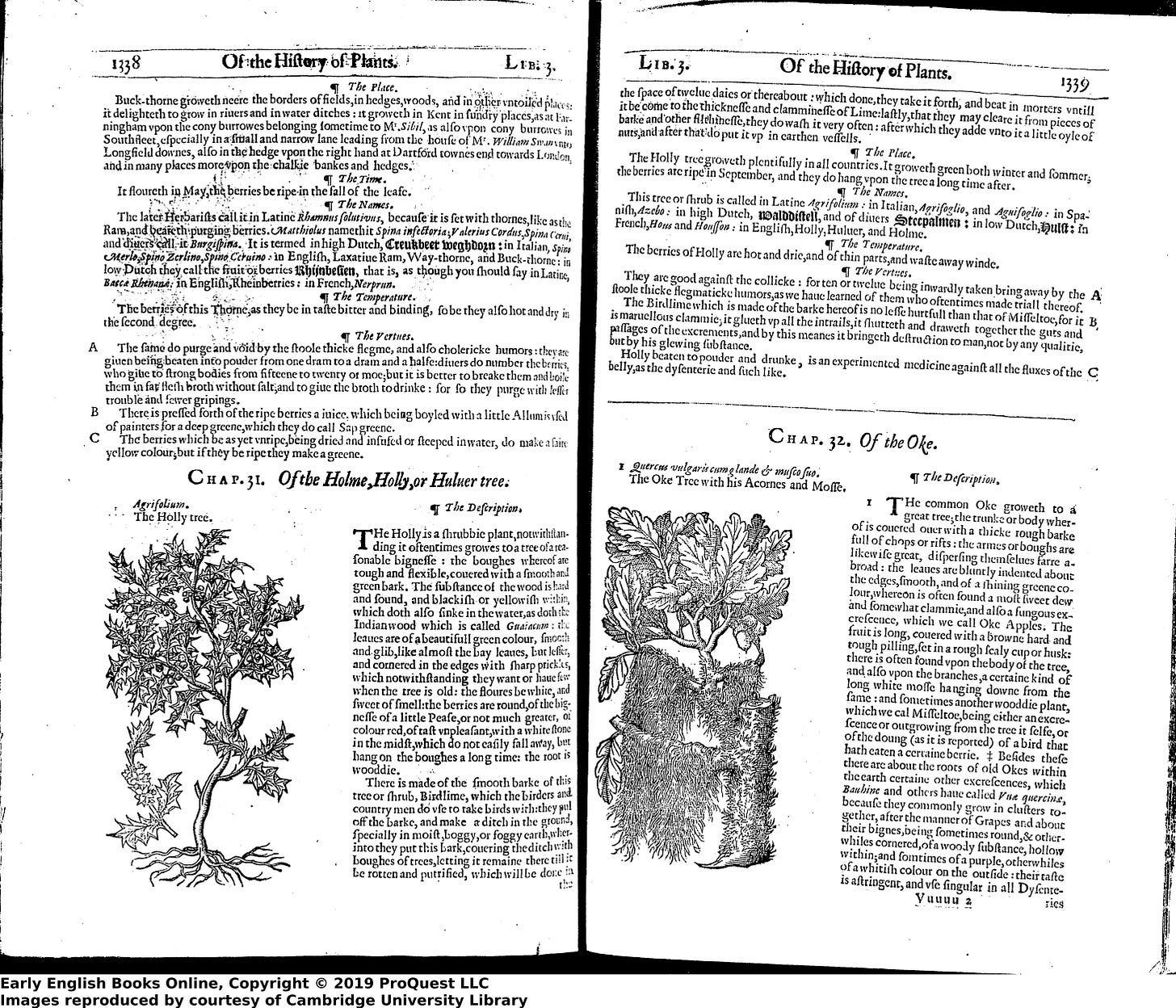

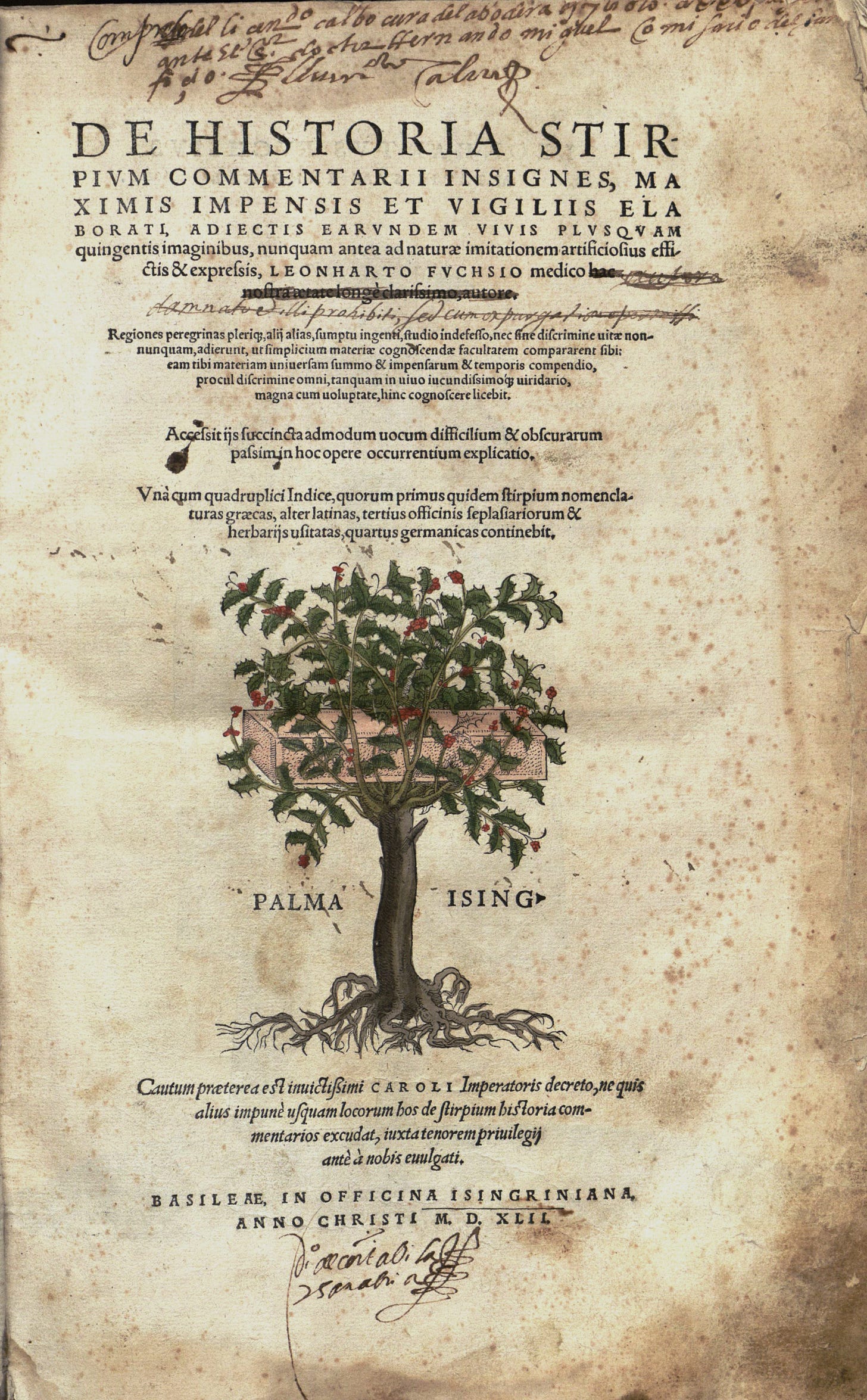

But for all our folksy familiarity with holly, there is a beautiful strangeness to the plant itself. It doesn’t grow in the Barber-Surgeons’ garden which inspired this newsletter, but as John Gerard writes in his Herball (1597), it “groweth plentifully in all countries.” Gerard also accurately identifies the principal physiological effect of eating holly berries, which is diarrhoea—to him, a purgative medical virtue, which will “bring away by the stoole thicke flegmaticke humors, as we haue learned of them who oftentimes made triall thereof” (pity the poor subjects of that particular “triall”). Holly is evergreen, but instead of needles it has leathery leaves, richly sea-green and shining. Gerard writes that “the leaues are of a beautifull green colour, smooth and glib, like almost the bay leaues, but lesser, and cornered in the edges with sharp prickes.” At this time of year, holly’s red berries are often the only ink-drop of colour against bare branches and washed-out skies. But there’s a double-edge to all this beauty and vitality: the leaves are prickly, the berries poisonous. It’s this duality which makes holly so useful in Christian symbology, which often turns on mirror images of pain and joy, each embedded within the other. Holly’s winter brightness associates it with the birth of Jesus, but its thorn-like leaves and blood-red berries augur the Passion.

This memento mori doubleness underlies Christmas itself, too. Amidst the cosiness and conviviality, there’s an inevitable introspection that comes with the long nights and the year’s looming turn. It’s an undertow that Dickens, obviously, captured in A Christmas Carol (1843), which dramatises the moral darkness for which Christmas cheer is meant to provide an antidote. Holly features in the story as backdrop and prop, but also memorably in a weirdly brutal image, slicing straight through layers of Victorian schmaltz and straight into pagan violence: the unreformed Scrooge rails that “every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips, should be…buried with a stake of holly through his heart.”

The idea that selfishness at Christmas invokes special moral punishment is much older than Dickens. In Bede’s Life of Cuthbert, for instance, there’s a vignette recounting Christmas of c.683 CE, when Cuthbert was living as a hermit, on an island near the famous monastery on Lindisfarne. A few of the Lindisfarne monks took it upon themselves to row over to Cuthbert with a feast, presumably not thinking through the attitudes towards unannounced guests that his island hermitude might imply. Still, they manage to cajole him out of his hut to eat. Once, twice, then three times, Cuthbert halts proceedings to warn everyone that they must resist temptation and repent. On the third interruption, the monks reluctantly decide that the atmosphere has been sufficiently ruined for them to bring the feast to an end. When they return to Lindisfarne the following day, for their sins, they find that one of their brothers has died of plague: “as it grew and became worse from day to day, yea and from month to month, and almost throughout the whole year, nearly the whole of that renowned congregation of spiritual fathers and brethren departed to be with the Lord in that pestilence.” Moral concern about the risk of contagious disease posed by travelling for over-indulgent Christmas celebrations with friends is, perhaps, nothing new.

ERRATUM: Thank you to the keen-eyed Miltonist who pointed out that the image of “Filme” over Adam’s eyes in Paradise Lost, quoted in my last email, may be less autobiographical than it appears. I am informed that “an identical image appears in Of Reformation’s first book, written long before Milton lost his sight:

‘If our understanding have a film of ignorance over it, or be blear with gazing on other false glisterings, what is that to truth? If we will but purge with sovereign eyesalve that intellectual ray which God hath planted in us, then we would believe the Scriptures protesting their own plainness and perspicuity, calling to them to be instructed, not only the wise and the learned, but the simple, the poor, the babes’ etc.”

Spottings of any other “false glisterings” in this and future newsletters are welcome.